Is My Child Safe at Lower-Ranked Schools?

Lower-ranked schools get a bad rap, but the research is mixed

This post contains content about bullying and school violence.

Ok, we’re diving into safety today. Before I get into the data, I want to recognize that many of us have first-hand experiences with ourselves or our children feeling unsafe, or have a friend or neighbor with a story related to bullying, drugs, violence, suicide, depression, or anxiety.

This post is not meant to demean or take away from those lived experiences. At the same time, I also want to recognize that fear is a powerful emotion, and sometimes those experiences can become larger-than-life in a local school or community. Today, we’re looking at what the research says more broadly in order to help make more informed decisions.

Last week, we discussed how income influences academic performance, as a way to help us better contextualize and understand school rankings. Lower socioeconomic status (SES) school tend to be lower-ranked through no fault of their own, and as a result, those schools often tend to have a reputation of not being safe, compared to wealthier, higher-ranked schools, like a private school.

Perceptions of drugs, increased behavioral problems, school violence and bullying are common when considering low-ranked schools, which tend to be more socio-economically and racially diverse. And often, the data seems to support those perceptions, with researchers finding clear links between poverty and school disorder:

“In a study conducted by Townsend Carlson (2006) on a sample of American adolescents, poverty was a significant predictor of violent victimization at school.

The results of this research indicate a correlation between the frequency of victimization and the socioeconomic status of the family from which the student comes, with students from poorer families at higher risk of violent victimization at school.”

Segregating low-income students together makes it worse:

“Within small neighborhood areas, grouping more disadvantaged students together in the same school increases total crime.”

From the U.S. Department of Justice:

“Approximately 19 percent of students attending public schools reported that gangs were present at their school, compared with 2 percent of students attending private schools”

City schools, historically more racially and economically diverse, tend to take the brunt of the criticism:

“A greater percentage of teachers in city schools (10 percent) reported being threatened with injury than teachers in town schools (7 percent) and suburban or rural schools (6 percent each)”

Given this data, is your child safe and secure at low-ranked schools, or would you be putting their wellbeing and sense of belonging at risk?

Violence, crime and bullying is decreasing in schools

Let’s take a step back and view the data in a broader context. Overall, the news is good. The U.S. Department of Justice indicates that crime and violence in schools has generally been decreasing for some time:

… Students are not often the victims of violent and serious violent crime in schools. These trends have been decreasing since 2001. Physical bullying victimization has also been on a downward trend since 2009-2010. Schools have reported fewer incidents of violent crime and serious violent crime, and these too have been on a downward trend since 2009-2010. School homicides, in comparison to other youth homicides, are relatively rare.

Report on Indicators of School Crime & Safety: 2021.

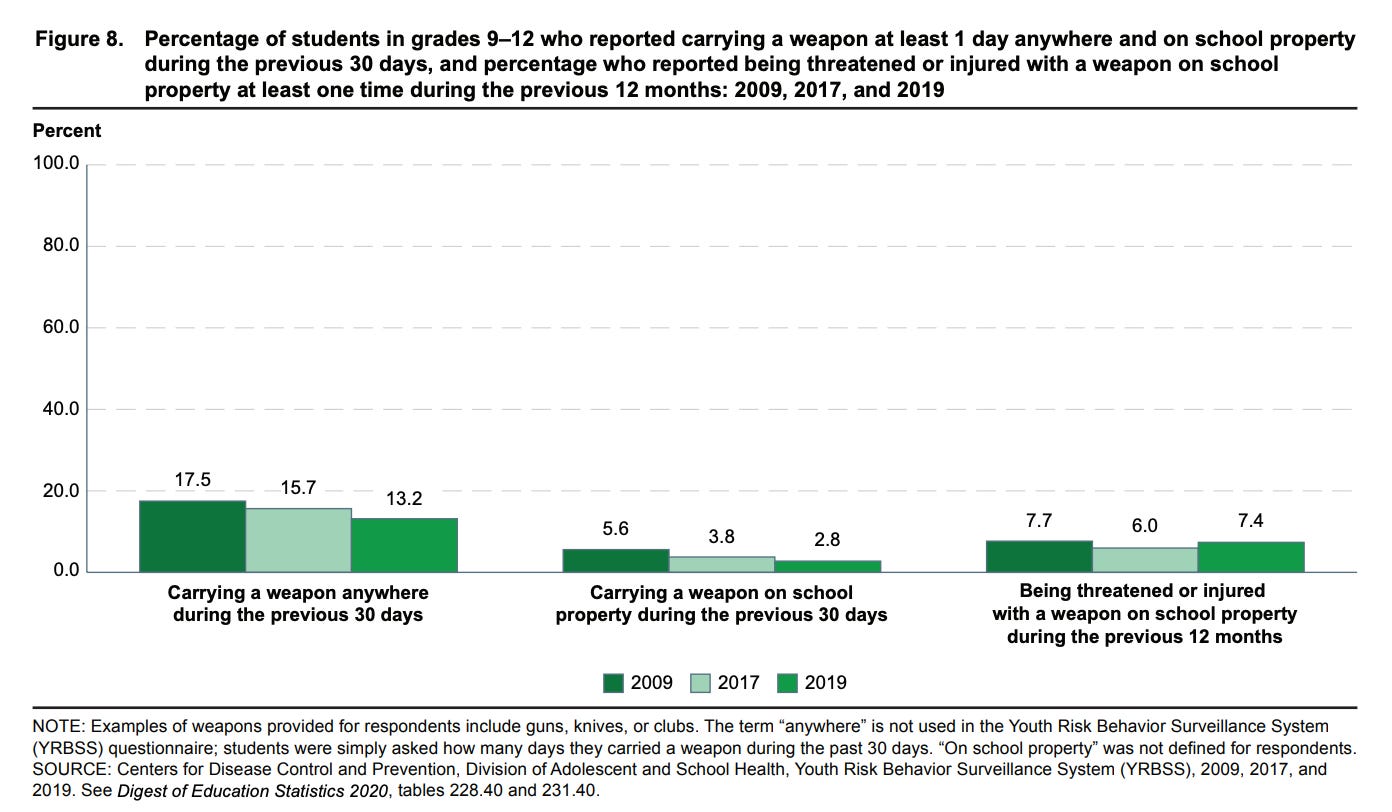

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCEI) reports similar declines: physical fights are down, students carrying weapons are down, alcohol use is down, bullying is down, criminal victimization is down, and threats and injuries are down.

Similarly, a new 2023 UCLA study of more than 6 million students in California during an 18-year period found “massive reductions in all forms of victimization,” including:

a 56% reduction in physical fights

a 70% reduction in reports of carrying a gun onto school grounds, and a 68% reduction in bringing other weapons, such as a knife, to school

a 59% reduction in being threatened by a weapon on school grounds

and larger declines in victimization reported by Black and Latino students compared to white students

Where parents may have cause for concern is cyberbullying, which has doubled in the past ten years as the usage of phones and social media platforms have become the norm.

School climate is a better predictor of a school’s safety, more than the student population’s income or race

However, several studies suggest that safety concerns around low socioeconomic status (SES) schools may be misplaced. The new 2023 UCLA study that I reference above? The co-author reports that:

“these findings [on massive reductions] were evident in more than 95% of California schools, in every county, and not in wealthy suburban schools only.”

A study out of Penn State in 2021 claims that safety concerns are unfounded when integrating wealthy students into more diverse schools:

“In fact, of all the survey scales that we looked at,” Peter Piazza reports, “the physical safety scale actually had the largest positive difference between white students in ‘diverse’ schools and white students in ‘not diverse’ schools.”

And a study in the Journal of School Health in 2011 found:

“High student performance on standardized tests does not buffer students from unsafe behavior, nor does living in a dangerous neighborhood necessarily lead to more drug use or violence within school walls. School climate seemed to explain the difference between schools in which students and faculty reported higher versus lower levels of violence and alcohol and other drug use.”

In fact, school climate appears to be more important than socioeconomic status. Much of the historical research on school violence has focused narrowly on disadvantaged youth, without examining other contextual factors that might influence violence and victimization. It turns out that simple and straightforward interventions like a good student-teacher ratio and clear communication make a big difference in increasing safety:

“Schools in which students perceived greater fairness and clarity of rules had less delinquent behavior and less student victimization.”

“Across all models, higher levels of teacher support were associated with lower rates of victimization.”

“Reducing the ratio of students to teachers and reducing the number of different students taught by the average teacher are likely to reduce student victimization”.

What doesn’t work? Researchers call it “punitive control:” interventions like surveillance, metal detectors, and heavy reliance on law enforcement and security personnel are found to be consistently unsuccessful.

Of course, the rub is that those measures are already concentrated in schools with high rates of ethnic non-White enrollment, leading to perceptions of greater violence and crime, perpetuating a vicious feedback loop that unfairly targets low socioeconomic students and the schools they attend.

Comparing higher and lower-ranked schools

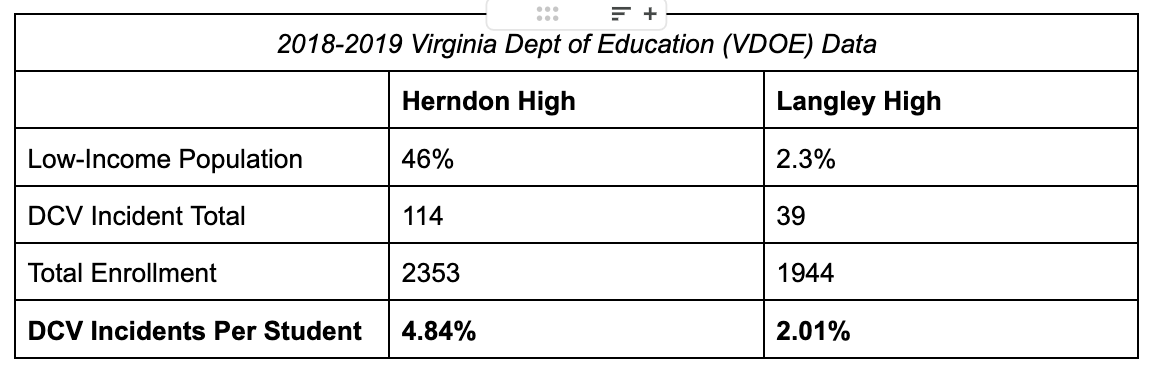

For our part in last week’s newsletter, we looked at the rankings of two high schools in Fairfax County and discovered that Langley is rated a 9, and Herndon is rated a 3. We showed how school rankings reflect a school’s demographics (Langley’s low-income population is 2.4 percent, while Herndon’s low-income population is 42 percent) more than how effective the school is at teaching your child.

Now let’s turn to safety. The Virginia Department of Education (VDOE) has historically required school divisions to submit data to the VDOE on incidents of Discipline, Crime and Violence (DCV), so we can compare our two schools that way.

In the 2018-2019 School Year, Herndon reported 114 DCV incidents, while Langley reported only 39 DCV incidents. It’s true that there were more incidents at Herndon, but their student enrollment is also higher. When looking at the percent of incidents per student, it’s less than five percent for Herndon and two percent at Langley, both very small numbers to say the least.

Source: Virginia Department of Education.

Note: we originally used 2020-2021 data for this comparison, but a reader pointed out the 2020-2021 school year was during the pandemic when most students were learning remotely; as a result, we’ve updated the data to 2018-2019. Thank you, Anne!

Summary

Let’s summarize what we know:

There are clear links between poverty and school disorder, but local research is needed in your community;

Crime, violence and bullying are decreasing in schools overall;

School climate is a better predictor of school safety than the socioeconomic status (SES) or racial demographics of a school’s population;

Simple interventions such as clear rules, follow-through and teacher support have positive impacts on increasing safety.

I’m planning to turn our attention to a new subject for next week’s newsletter, but I promise to revisit school safety, with a deep dive on drugs and mental health in lower-ranked versus higher-ranked schools in the upcoming weeks.

Until then, please like this post if you found it useful or interesting, and drop a comment below with something you learned or are curious about. I love to hear from you.

very interesting! one thought to add: are higher income schools more apt to not report - i.e. parents talk with school administrations about not reporting and giving more chances to these students ? so less VDOE tracking/reporting. also, in my review of VDOE stats - Herndon Middle had higher #'s of incidents but you are finding lower #'s at Herndon High - so would be interesting to understand the differences in age groups too.

I've been keeping my eyes peeled on my inbox for this series. There hasn't been any new article since this one came out, right?